Tuesday, December 30, 2008

Quaker Ontology

Mark quite rightly called me on name-calling. I said "But here I am, gettin' pissed off. And not against small-minded, homophobic, hate-filled, cling-to-guns-and-bibles, fire-and-brimstone Christians." My intent was to say I was not getting angry at our typical liberal strawman, the evangelical. And I should point out that I was not saying "Christians are small-minded, homophobic, filled with hate, cling to guns and bibles, and spout fire and brimstone." I'd say none of my self-identifying Christian friends exhibit any of these qualities.

So why was that name-calling? Because I was conjuring up a sub group of Christians, identifying them, and then smearing them. I was doing the same thing the Outgoing Occupant has done in defining our countries' enemies as "terrorists." I was simultaneously creating an identity group and tarring it wholesale.

"Name-calling" is a weird phrase. I call all kinds of things by name, not all of them names they had before (I've been reading Roald Dahl's The BFG to our son and am greatly enjoying the BFG's wholesale creation of new words for things like snozzcumbers). But calling something by name is different than name-calling. Or is it?

When I decided to request membership the Society of Friends, I was asking to be recognized with a name, Quaker. I was accepting that I was growing into being part of an identity group. Membership is a formal process, but it usually reflects a longer informal process of becoming. The question is, though, what are we becoming? That's where a lot of the current sturm and drang comes from, I think. At least that's the root of my sturm and drang.

I don't believe I am becoming a Christian. I am in an environment, both in my marriage and in meeting, where I am in communion with Christians, but I do not identify as one and am uninterested in being identified as one. Now, I have absorbed much of the story, the teachings and the example of Jesus, but I have absorbed a lot of other stories, and I do not wish to privelege Jesus's stories above others I find meaningful, nor his life, nor his teachings.

And I do not like feeling I must define myself as a "non-Christian Quaker," any more than I like being labeled a "non-theist." Which is about as much as a Christian Quaker would like to be defined as a "non-secularist" or a "non-humanist" or a "non-snozzwangler." No one likes to be defined by a negative, at root. And yet here we are, Protestant (protesting against the Roman church), non-theist/a-theist, secularist (not sacred) type people. I like being able to say I am a Quaker. I plan to keep saying it.

Well, probably I plan to. Here's the problem for me: by naming myself part of this identity group, I risk making membership in the group more important than truth. I think this is a risk in any group, and indeed any naming: we name something, or measure something, and then we apply the name or measurement back onto the thing itself. It's a basic human trait, certainly not particular to Friends, but it's one that especially in other conversations on this blog I am growing to recognize as inherently destructive of perceiving truth.

In this instance, we are Quakers because we say we are Quakers. We come together. But then we try to ferret out what exactly we have in common as Quakers. Once we have decided that, what happens when one of our number, or we ourselves, deviate from that definition? We are forced (or force ourselves) to get back in line, or are shown (or show ourselves) the back door.

And why is this? What makes this happen? I think it is, simply, human nature. We form groups. We want to reassure ourselves, through formalizing, that these groups have some basis in meaning, that they have definition. And once we are assured of this, we don't want to let it go. I've certainly seen, in myself and others in meeting, a deep anxiety over not maintaining some sort of definition. Just letting it be, letting just anybody (or any idea) in makes the experience of our community and its work somehow paler and less interesting. Emptier.

I hold this up. I've got no answer. It's a Quandary and a Query. It warrants more sitting with, I think.

Saturday, December 27, 2008

The Quaker Paradox

Mark Wutka raised a comment on my last post:

I understand that you don't want to think of yourself as bigoted, but I think you should take another look at the phrase "small-minded, homophobic, hate-filled, cling-to-guns-and-bibles, fire-and-brimstone Christians".I responded

About my snide comment about "small-minded, homophobic, hate-filled, cling-to-guns-and-bibles, fire-and-brimstone Christians." Guilty as charged. I am bigoted against the Rev Phelps' followers, and against people who teach Hell as a way to persuade [kids] to sign on with the church, or who believe that killing an infidel is the way to heaven. Yup. May they know peace and love, and please keep them out of my family's life as much as possible.To which Mark responded:

Does it not strike you as at least ironic that you can be so unabashedly bigoted against a particular religious group when you are so committed to theological diversity? At what point do theological differences outweigh the commitment to diversity?My answer is, Yep. I called it the Quaker Paradox in high school, though it isn't really a paradox, but a quandary: how do you live up to an ideal of tolerating, even embracing theological diversity, when some of those you are tolerating are, in fact explicitly out to get you. Snake handlers aside, how do we deal with Reverend Phelpses? Around the time I joined, Twin Cities Meeting asked someone not to return after she made some extremely heartfelt but (to many present) hurtful and even threatening statements in meeting about homosexuality. How do we feel about pre-Columbian Aztec theology? Are we bigoted if we oppose live human sacrifice. Obviously this is an extreme example, but it does bring practice right smack up against theory.

In theory, I like to think of myself as not bigoted, but, yes, there are degrees of spiritual familiarity. Liberal Methodists, sure, I can have an extremely civilized conversation with. Mel Gibson's brand of Catholic, a harder stretch. The Taliban? Honestly no, I would not try to stretch.

The point I think needs to be made is that theology has flesh and blood consequences. If we ask ourselves and each other to live out our theological understandings, then we should expect no less of those whose theology includes heavy doses of fear and loathing. And this can in fact threaten us. Probably not as quickly as we believe it will, and probably not as much as we fear it does, but that doesn't mean there is no threat. And so we need to ask ourselves if we are willing to invite in that sort of ideology (he says as if there is a good sort and a bad sort and the bad sort is easily identifiable by its green skin and habit of saying "I'll get you my pretty!"). Are each of us actually ready to be a Mary Dyer?

I'm not. Sorry.

Friday, December 26, 2008

Gettin' ticked off for mysterious reasons

What the hey? Where on earth is this bitter anger coming from? No one's really stomped on my religious liberties lately. If anything, my respect for and understanding of honest, deeply felt personal religious faith has grown a lot over the last few years.

But when the question turns to whether we as a community identify as Christian, my dander mysteriously rises like hair on the back of a dog in the seconds before an earthquake.

What on earth?

A clue: in my argument with my wife, she felt the same feeling of personal threat, only in her eyes it was me telling her she wasn't allowed to express her beliefs. So it's not simply a matter of feeling trapped by the patriarchal hegemonizing colonialist bully-boy politics of evangelical theology. (Did I get all the key words in there? I feel like I've forgotten one. Oh, right, I forgot to weave the word "power" in there somewhere.) It's personal, not institutional.

Another clue: What struck me initially as I really try to get hold of this anger is how much it feels like not being picked for the middle-school softball team. Now, some of the language some religionists use to discuss matters of group identity are explicitly about "you're on the team bound for heaven; they're didn't make the cut and are going to hell," but that is not the case here. In fact, in all the discussions in my family, in Friends meeting, among friends, there is an explicit statement like "we're all on the same team here, and we don't believe in Hell, and the afterlife is an open question, and we love and support each other." But somehow following this up with a question like "What's our team song?" sets off some weird stuff.

Yesterday, Ingrid mentioned what to me felt like a sharp wedge cracking into what's going on: she was observing how, from a kind-of-Buddhist sensibility, we all hang on to our sufferings. If someone has done us wrong, we remember it, tenaciously. We make it part of ourselves.

Now, I was not raised oppressed. No secret churches under threat from the secret police for me, no razzing at school for wearing religious paraphernalia (not sure what paraphernalia I would have worn anyway—gold question mark on a chain?). My parents tsked and winced at televangelists and crazed imams, but we were not the Madalyn Murray O'Hair family in any sense. Secular, but not crazy. Heck, my parents met at a Unitarian church and were happy at my getting some sort of religious background at my high school.

So what kind of suffering am I remembering? And what am I getting so mad at now?

I think it has to do with trust.

Here's the thing: the biggest freak-outs I can remember having have to do with physical trust exercises: the kind where you stand up on a platform and fall backwards into the rest of the team's outstretched arms. Or where you have to get the team members up and over a tree limb. The last time I tried one of these was back in high school. Freshman orientation, actually, so I was 14. And I just freaked. I lost it. I don't remember all what happened, but there were tears, and as I recall, I was the only one who really freaked this way.

I am lousy at situations where I can't put my feet on the floor, metaphorically or literally speaking. I hate swimming in over-my-head water. I hate being on the edge of a roof. And apparently, I need to keep my own feet under me religiously as well.

I absolutely see that being able to off-load your troubles/trespasses/moral compass to another is very helpful. I visit in prison, and have seen repeatedly how getting religion helps ground folks, gives them a sense of not being out there on their own. I think Jesse Ventura was profoundly messed up when he talked about religion as a crutch and preached the gospel of self-sufficiency. None of us are self-sufficient, but some of us are better than others about giving credit for being held up.

But there's a point at which, to me and a lot of other folks, there's such a thing as too much faith, too much off-loading of responsibility. The Ben Franklin mantra, "God helps those who help themselves" comes to mind. Or the joke about the man who trusted in God to help him win the lottery, only to be dressed down from above for not actually buying a ticket.

So what the heck has this to do with me being pissed off at Christians? Or my wife being pissed off at secularists?

Simple. We don't trust others to hold our spirit up. We don't want to put much of our weight onto a foreign spiritual language, or a foreign set of stories and theologies. We my love our neighbor, our fellow member of Meeting, our spouse even, but we need to feel our own feet planted under us.

When someone asks us to name their religious basis as our own, they're in essence asking us to do that trust exercise where everyone sits on everyone else's laps, in a circle. Except that it feels to each of us like everyone else is sitting on some pretty unstable ground. When we're being Universalist about it, we can shrug and be philosophical about other people: you stand on your self, I'll stand on mine, and we'll each take our chances and love each other just the same.

But when it comes right down to it, we like our own foundations, and we're not interested in jumping off them. Which is what making a statement about universalism feels like to some, about Christianity feels like to others.

No answers to this one, folks. Just a survey of the landscape.

Thursday, December 18, 2008

Naturalized

Douglas uses a few examples: sexual duality and the entirely "natural" exceptions to that statistical norm; the idea of competition as the basis for natural selection (again, a common factor in evolution but apparently originating as a "natural law" in nineteenth-century views of human nature); the transition of exceptional anomalies in human development ("monsters" in popular usage) from atypical "wonders" into being seen as "abnormal" and therefore "mal-formed."

Then he hits us with (to my mind) the big one:

The difference between anomaly and abnormality is basically the difference between pattern and expectation. Similarly, the error with male-and-female is primarily expecting intersexes, hermaphrodites and polysexes to fit the male/female categories because those categories are, or seem, pre-established. In our competitive culture, who is positioned to recognize competition as anything but an expected foundational principle? The errors, then, are ultimately not just about sex or development or natural selection. They are all about expecting nature to adhere to strict rules. That, in turn, is based on assuming a fundamental and enduring universal order. This expectation itself represents, I contend, yet another naturalizing error: the very concept of laws of nature.Douglas argues essentially that we have created unchangeable laws of nature where there may be no laws, that the very idea of laws is rooted in our cultural or more generally human biases.

Recently, historians have profiled the cultural and religious context that guided the origin of the modern/Western concept of laws of nature (Steinle 2002 [also an interesting read; it's available in part here]). Here, I want only to draw attention to how powerful a hold the concept of laws of nature has on our minds. The very language is highly charged. In human society, laws specify what we ought to do. They ensure social order. We tend to interpret laws of nature in the same way, as guaranteeing the natural order. Laws of nature profile how nature should act. Once established, descriptive laws take on a prescriptive character. Pattern becomes expectation. This is how local regularities, or the familiar, or the "normal," become naturalized.I think this relationship between description and prescription (or proscription) reflects on the earlier discussion of "the grid."

And on a lot of other notions of ordered systems.

Profound stuff. The whole paper bears a close reading. Thanks Douglas.

Saturday, December 13, 2008

Pragmatism

Yup.In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, “pragmatists” of all stripes–Alan Dershowitz, Richard Posner–lined up to offer tips and strategies on how best to implement a practical and effective torture regime; but ideologues said no torture, no exceptions. Same goes for the Iraq War, which many “pragmatic” lawmakers–Hillary Clinton, Arlen Specter–voted for and which ideologues across the political spectrum, from Ron Paul to Bernie Sanders, opposed. Of course, by any reckoning, the war didn’t work. That is, it failed to be a practical, nonideological improvement to the nation’s security. This, despite the fact that so many willed themselves to believe that the benefits would clearly outweigh the costs. Principle is often pragmatism’s guardian. Particularly at times of crisis, when a polity succumbs to collective madness or delusion, it is only the obstinate ideologues who refuse to go along. Expediency may be a virtue in virtuous times, but it’s a vice in vicious ones.

There’s another problem with the fetishization of the pragmatic, which is the brute fact that, at some level, ideology is inescapable. Obama may have told Steve Kroft that he’s solely interested in “what works,” but what constitutes “working” is not self-evident and, indeed, is impossible to detach from some worldview and set of principles. Alan Greenspan, of all people, made this point deftly while testifying before Henry Waxman’s House Oversight Committee. Waxman asked Greenspan, “Do you feel that your ideology pushed you to make decisions that you wish you had not made?” To which Greenspan responded, “Well, remember that what an ideology is, is a conceptual framework with the way people deal with reality. Everyone has one. You have to–to exist, you need an ideology. The question is whether it is accurate or not.”

Guest Post: Keith Harrison

The Subj/Obj opposition has puzzled me since the time I heard an English teacher call a poem by Shelley ‘a subjective lyric’. I couldn’t understand what he meant, and said so, and learned nothing from his reply. Much later, reading Bronowski and Polyani, and a host of others, I got thinking about it again. I believe (especially since Heisenberg) it’s a pseudo-distinction, and certainly in the humanities a useless pis-aller. Whether in cartography or poetry I believe all we can do is to give versions of that part of the world which takes our attention. In spite of what many scientists actually assume in their practice, if not in their belief-system, there’s no god’s eye view of the world. We are not (at our best??) cameras, for reasons that should be transparent to anyone who thinks a little about it. Scientists hate that thought because it ushers in the dreaded C-Word as Murray Gell-Man puts it. What in the hell do we do with consciousness, which is after all the most fundamental fact of our being here? The answer that scientists often give is that you have to regard it, as Freud does the mind, as an epi-phenomenon of the body. Or, in the case of Crick, you dismiss the question as trivial. Generally speaking, you’re better off to forget about it and get on with the "real work". The trouble is that, as writers, we can’t do that because it doesn’t make sense. We are here and we have to tell stories - all kinds of stories - about what we experience. Part of my brief is that because we have been trained to think of ourselves as non-persons and because we have tried hard to do that, the result is the kind of prose that pours out of our colleges by the truck-load. In most student-essays there’s nobody home and when you ask the simple question— where did this dogma of ‘impersonality’ come from?—it’s not possible to find a satisfactory answer, except: we have always done it that way. But if essays are really forms of narration (stories), questions of accuracy inevitably arise. Why is my version of the auto bail-out more accurate than another’s? Or less? Interesting questions. Not, I would maintain because mine is more objective (whatever that means) but maybe because it has a wider explanatory range, because it is more consistent with many other ‘explanations.’. Consistency does seem to be a key, but clearly not a self-sufficient one (people used to be consistent about phlogiston). I could go on but will stop (on this question) with this: there seems to me nothing wrong with either a scientist or any other person declaring him or herself to be a largely ignorant person trying to make a somewhat intelligible "version" of one part of the world we all live in. Yet our dominies, our Strunks and Whites, and the greater part of our professoriat, would argue very strenuously against that assumption. We must tell the truth, be objective etc. There’s always the ghost in the machine, even when we take God away. The belief is very powerful. Someone must know the truth. It’s got to be there. Doesn’t it? Even Dawkins fall for the delusion.Whew.

Now for something provocative. I’m more and more convinced that beneath all our professional ‘belief’ in objectivity, five-paras, the forbidden ‘I’, and on an on, is a deeply entrenched commitment to the status quo. In other words that commitment is based a political belief which is almost invisible and, because of that, all the more powerful. This is the elephant in the room. We have taken our binary oppositions (heredity v. environment, nature v. culture) so much for granted that we’ve become stupefied and stunted in our thinking on very important matters. When one considers the brief given implicitly to most student writers, but NEVER examined, it goes something like this: You don’t know much about the recent history of Madagascar but your task is to write about it AS IF you do know something about it (you will get the vast bulk of your knowledge from sources, of course) and AT THE SAME TIME you should write as if you are not a person and must never use the first person. The brief is doubly incoherent at root. No wonder students hate writing essays but being, essentially, survivors they will find the best way to get under the wire. The most common practice is to string together a series of ‘quotes’ (properly acknowledged, of course) and to try to give the impression that the essay has an author, but not really, because the ‘author’ doesn’t really know anything. One can hardly imagine a more futile dry loop, a more complete waste of time. To ‘succeed’ in this exercise requires an imagination as dense as that of George Bush or Bill Kristol or Larry Summers. It’s main driving power is an unflinching commitment NOT TO THINK.

Against this ‘method’ of writing a paper I would propose the following. Get interested, get very interested in a topic, put yourself on the line as you think about it. Work. (If you can’t find a topic please do something else. Anything. But DON’T start writing until you are really involved.) Stand firm in your own partial knowledge, ask real questions. Use you genuine ignorance as your strength. Explore. Use quotations to help shape your own ideas, questions, puzzles. This is your essay it cannot be written by your sources. Use your essay as an authentic exploration of a question which matters to you. Remember that most teachers cannot write. They have been trained to think in very proscribed modes for reasons which become clear as you think about the whole purpose of education which, in the words of our some time Governor, Arnie Carlson, is to produce ‘successful units for deployment in the economic sphere.’

You were surprised by my ‘weird’ ideas on outlining. Another reader was delighted to find that it’s okay to use the first person in an essay, a third felt relieved that it’s alright to end her essay at the end and not at the beginning as she usually does. More questions: what do the words ‘alright’ and ‘okay’ mean in these sentences? More still: a university is a place where we should ask questions, sure. But not questions about sacred matters like this, or patriotism, and on and on.

In the teeth of all the conformism I have found in fifty years of teaching I want to join in the exciting task of helping students be authentic persons, in whatever they do. We (all students) have to give ourselves permission to be alive, questioning, foibled, ignorant, occasionally savvy, always fully ‘here’. Bloody difficult task. Our systems have made it an almost impossible one. Most schools have a corpse in the basement, and another one in the brain-pan. (Another full essay needed here). To cut to the essential thought: A revolution, what Blake called a Mental War, seems necessary.

And there you have, in sum, his new book. My only comment (I viscerally agree with most of what Keith says) is to go back to objectivism (the cult of objectivity) as a way of creating common ground based in verifiable experience. Whatever the culture of science may have become (and I hope to have more to say on this soon), the basic fundamental core of science is the idea of repeatable experiment. And the idea of objectivity comes out of this sense that if I drop two cannonballs from the Tower of Pisa, from the second of planet Foozbain, or the top of Mount Doom, they will land on the ground at the same time, regardless of their varying mass. This skeleton of "verifiable facts" seems to me to be the basis of the whole shooting match: the langauge of cartography, the voiceless essay, journalistic objectivity...

It's all pidgin, and placed against the previous context of a common language based on divine and miraculous explanations for things, it makes a lot of sense. It makes conversations about practical matters possible for a broader range of people. The trouble comes when we start wanting to insert lyrical, subjective content into this pidgin, because that content is adamantly non-repeatable. Conversely, we can get in trouble if we hide behind "objectivity" in order to get our selfish way (see Woods' critique of cartography).

And when we insist that all discourse be carried out under this rubric, even when what we are talking about doesn't need the pidgin to be able to cross a cultural divide, we (as Keith points out) stifle real creative work, which needs to be carried out by a whole person, not just the part that can be translated into pidgin.

Monday, November 17, 2008

zoomy zoomy zoom

There's the opening sequence of the Carl Sagan-based movie Contact. And there's a sequence from the Imax movie Cosmic Voyage.

The one I remember best was on a poster for the Carl Sagan TV series Cosmos, in the early 80's. This was essentially based on Charles and Ray Eames' 1977 short film, Powers of 10.

And this in turn has an inspiration in Kees Boeke's 1957 children's book Cosmic view; the universe in 40 jumps. Instead of using photographic imagery, Boeke uses cartographic, drawn images both when moving out beyond aerial photography and when moving in to the level of a mosquito.

This zoom in/zoom out idea makes continuous what in our everyday experience is a blurry line between familiar and unfamiliar. We are lifted (and compressed) from the familiar to the unfamiliar.

The scale we work in the "real world" at any given moment is at most a millimeter in precision (threading a needle), or a square kilometer in breadth (the view from a hillside). Beyond these distances (more or less), 1,000,000 times the other in order of magnitude, we can work but only with aids: microscopes on one hand, transport on the other. And in terms of geographic space, we can work over time across a larger area.

To push these natural limits of scale is and always has been a sort of magic. I've been working for some time on the bird's eye view artist John Bachmann [the paper will be published in the January issue of Imprint, but I'll set up a page with links to Bachmann's images available on line, sometime this year.] Bachmann's magic at his time was the creation of views from the point of view of a bird, at a time when no photographs had been taken from the air (the earliest surviving air photo is from 1860 of Boston). His views, and all nineteenth-century and earlier bird's eye views are works of imagination, carefully constructed from bits and pieces of ground-gathered evidence.

As zoom-in-zoom-out becomes the norm on line, it continues to blur the difference between a map that reflects our direct experience and a map that shows what is essentially alien to that experience. Sometimes (as with Google Earth) the experience mimics rising and falling from a (marked up) earth's surface. Sometimes the zoom is clearly like looking at an artificial picture (note how Google Maps zooms out to an infinitely repeating Mercator projection).

Multi-scale map systems were a subject of some discussion at NACIS this year, notably with Penn State's ScaleMaster project, which is really as much a project organizer as as anything; letting multi-scale project organizers set guidelines for when to reorganize what data. Making cartographically sophisticated map system at multiple zoom levels is a new thing, and a growing thing. We think of it as different than an animated map, becasue we are creating static images that users move around, but the experience of using the maps in effect is animation. And it would be good for us to bear that in mind as the field expands...

Sunday, November 16, 2008

45°NE

I'm embarking on an experiment.Any and all advice or commentary is welcome.

I've been ruminating for a long time about how to express sense of place in maps (I'm a cartographer).

For a few years I've been thinking about how to channel experience of place into a form true both to the objectivity-seeking values of cartography and the personal-expression values of the fine arts (I was a studio arts major in college).

And I've been trying to think of a way to use the 45° N latitude line that runs a block and a half south of my office, right across the Northeast Minneapolis Arts District.

After a thought provoking time at NACIS, I reached the conclusion that the way to open up that 45°N line to experience was through some combination of exploration (more mundanely, "fieldwork") and pilgrimage. In one, there is a specific subset of information one looks to gather; in the other, one is looking for an opening to (in religious terms) grace, the miraculous, the other... the unexpected.

So.

I'm going to start regular monthly traverses of the line, beginning at Central Avenue, walking to the river. I'm going to record the results here. I hope to do the traverses with a variety of people, and in between to contact property owners to discuss with them how the line traverses their property.

Here's a crude GoogleMaps base of the traverse (the blue line shows the approximate actual line; the red shows my estimate of a walkable line on public right of way).

Anyone who wants to join me, drop me a line! Probably the easiest way is via my work email form. Or my cell phone (612-702-1333).

Tuesday, November 11, 2008

The Tattoo-Rumba Man

I was a Studio Art major at Carleton College. I had a fascination with northern Renaissance painting, especially folks like Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden, whose paintings are essentially visual texts: they are composed of symbolic elements posed to make a theological statement, within an illusionistic "window" into a sacred world.

My senior comps project was designed around this idea of art as text, based on texts and functioning as adjuncts to text. My problem: I didn't have a religious text I believed in as deeply as the painters of 500 years ago.

So I decided to write one. I had some examples of student-written stream-of-consciousness stuff I really liked, and some bits of text I was thinking of as kind of central to me, but it was my friend Adam sending me a scrap of text about the Tattoo-Rumba Man that got me going. I took it and ran (with his permission).

I still like the character, twenty years on, and I recently pulled out the text I wrote (it was edited somewhat over the following three years and then it lay fallow on various hard drives after 1991). It needed some tweaking, but I kinda like it, so I put it up on the web. Enjoy!

home.mindspring.com/~nat.case/id12.html

[After the fact, there was a scene in Strictly Ballroom that to me is the Tattoo-Rumba Man. See here and go to 8:20 on the timer]

Sunday, November 9, 2008

Porn

Frankly I find sexual pornography and such really really weird. Never understood the appeal except for the obvious: a source of stimulus. It looks from here like a kind of dead end of expression.

But it occurs to me that some of the early discussion about the experience of scale in cartography may have some bearing here, in terms of the size of the group one is working within. What I mean is, the social context of porn is not that of a long-term monogamous relationship, but of a larger social group. The characters typically do not know each other well, but are not totally anonymous (that would be rape). They are interacting sexually within a larger but identifiable social context.

[The following is probably all deeply covered in Sociology 101 textbooks, but I took Anthropology 101 instead, so I'm making it up out of whole cloth]

I'm going to theorize a scale of social interaction, starting at "nucleus," which is long-term partnerships of 2-5 people, or maybe a couple more (Well, actually we should start with "personal" where the social group is one). The next step up would be "clan" or "team", for groups of 6-20, which work together for a year or three. Next would be "village" or "congregation," groups of 30-200 centered around a physical location but with widely varying sensibilities, but with no members (unless there is a professional leader) actually knowing everyone in the group. Somewhere on up the scale is "nation," a group of 100,000 or more where the members share some basic common cultural facet of identity but little common social activity. Still further up the scale would be "species" and "planet."

The point is, scale determines what kind of interaction is expected. And a lot of this expectation is culturally driven: I expect sex to be at the nucleus level, and it seems alien to me when it is part of a clan structure or (as with porn) at the village level, with no intimacy and no deep knowledge between the partners. But certainly there are those for whom this is satisfying.

Cartography is about the experience of space at (minimally) a village level, more likely a national or planet level. What I and Steven and Margaret and Mike have been talking about is using the language of cartography at clan or nucleus level. But the social expectations surrounding this sort of land-talk are going to be as big as the porn divide. Steven's experience in trying to talk from an arts/experiential point of view to cartographers over the long haul has, I think been alien in this way, but I see his point of view slowly making its way into the sensibility of the cartographic community.

In religious terms, I think something similar goes on in the difference between individual mystical experience, small-group worship, and large-scale corporate worship. If we've grown into one scale of experience, it requires a difficult sort of open-mindedness to accept the validity of experience at another scale, particularly a scale that is orders of magnitude different.

I admit to bringing porn into the discussion partly for shock value, but I think the visceral discomfort many of us feel around porn is precisely the sort of conceptual dislocation we've run into here, in talking about the grid, and in talking in general about cartography.

Tuesday, November 4, 2008

Election Day 2008

That's all. Over and out.

Friday, October 24, 2008

The Power of Place

De Blij is a professor at Michigan State and a public advocate for geography—his previous book was Why Geography Matters... Not someting I like I needed to be persuaded of, but I gather there are a fair number of people who really do think geography really doesn’t matter, so good for him.

I was attracted, honestly, by the title, and I was disappointed to find that place itself and its power was not really described. There is no topography (in the old sense) here, no “sense of place.”

What this book is about is the importance of location. De Blij’s point is that regional variations in health, religion, language, exposure to natural hazards, etc. are huge determinants in your economic and physical well-being—quality of life. Well, to coin a phrase, duhhhh.

The piece that stuck out for me the most was his approach to religion. De Blij is not a religionist, and he picks out religious conservatism, especially conservative Islam, for particular critique. Now, I’m no fan of Wahhabi ideology (or of the fiery fundamentalism of any faith), but that this sticks so especially in his craw I think relates to of the weakness of the whole book: a limit in scale to his view. In cartographic terms, he never gets closer in than 1:100,000, and mostly he’s hovering above 1:1,000,000 (the scale of a US state road map). When he does zoom in, it’s for a few peculiarly impersonal snapshots, in particular a view of his native Netherlands from below sea level.

De Blij sees local conditions as trapping people, keeping them out of the benefits of a global marketplace. He fails to address seriously the appeal of localism: the way a close relationship with a place can yield an understanding and an attachment whose richness can more then counterbalance the economic benefits of mobility.

The appeal of religion is in the experience, the day-to-day living it. Same thing with place: the appeal is getting to know the place, learning to see it not as a ground to put your feet on, but as ground that supports you, as a thing itself. “Religion” itself is an “outside” word, as I think I’ve noted before.In the sense we and de Blij use it, it is a name for a system, like a state. When you live within it, it usually is not the state you are paying most attention to, it’s the places within that state. And it’s the visceral love for those places that politicians use to translate into love of country.

Religion has much the same dynamic as place: when it develops deep roots (and de Blij advocates keeping children from being “indoctrinated” until they are old enough to develop judgment), it ties people to itself with roots of habit, knowledge, and comfort. This becomes a “trap” only if the basis of the person’s attachment is a lie (e.g. a prophet who it turns out is a shyster who runs off to the Bahamas with all your money). The same imbalance holds when a person’s attachment to place is physically unsustainable—the heartbreak of resource-extraction economies forcing families to move once the resource is tapped out.

Where people are seemingly traped by their geography or religion, it is not the place or the spiritual life itself that is the problem usually, it is the socal construct built up around it. And unless we learn to respect the deep connections at the core of that construct, we will be approaching issues of global culture and its effect in as dark an ignorance as a madrassa student approaching a Western university or a hick visiting New York.

Monday, October 20, 2008

Corlis Benefideo

It's a story about a cartographer—a sort of platonic ideal of a cartographer—and writer named Corlis Benefideo. If you haven't read it before, please do. You can read it in his short story collection Light Action in the Caribbean, or pay $2100 for the limited edition by Charles Hobson (again, scroll down), or (I haven't done this but I hear his reading is great) listen to Lopez reading the story.

Go on, read it.

OK, so when I talked about the story last year on CartoTalk, I was unsure about the whole cartographer as ideal hero thing. I'm still not sure, although as Martin Gamache said on that thread, there is a part of me wants to "drink the Koolaid."

What got me this time, in a way it hadn't before, was not so much the wonderful maps Benefideo makes, as it is his revelation of the narrator's situation. From near the end of the story, Benefideo says to the narrator:

“You represent a questing but lost generation of people. I think you know what I mean. You made it clear this morning, talking nostalgically about my books, that you think an elegant order has disappeared, something that shows the way.” We were standing at the corner of the dining table with our hands on the chair backs. “It's wonderful, of course, that you brought your daughter into the conversation tonight, and certainly we're both going to have to depend on her, on her thinking. But the real question, now, is what will you do? Because you can't expect her to take up something you wish for yourself, a way of seeing the world. You send her here, if it turns out to be what she wants, but don't make the mistake of thinking you, or I or anyone, knows how the world is meant to work. The world is a miracle, unfolding in the pitch dark. We're lighting candles. Those maps—they are my candles. And I can't extinguish them for anyone.”There's a lot packed into that paragraph, and so it's easy to gloss over in the flow of reading fiction.

Benefideo is pointing out our love for "maps the way they used to be made" and that, to the contrary, he is making them not like he was taught, but as he thinks they ought. For all the trappings of old-fashioned tools and craft, he is in fact exploring new territory.

The middle bit echoed for me the old Quaker bit, Margaret Fell quoting George Fox's preaching "What canst thou say?" Except instead of scripture it's pointing to our received knowledge othe world. It's easy and quick to gloss over this as a typical challenge to go out and do good, but it's more subtle than that.

It's a conscious rejection of the idea of "reference" which forms the backbone of the idea of cartography—the idea that there is a certain set of facts about the world that we can start with. It makes reference a much more fluid concept. That bit about lighting candles in the pitch blackness reveals Benefideo not as some sort of super-perceptual being who is expressing what he knows. He is really an explorer who knows nothing but records what he finds.

[edited 2-17-13 to update links to the story]

Thursday, October 16, 2008

I wish I spoke Hungarian

Which is a long way of saying I have absolutely no idea what this fellow is saying about me or anything else. I like the picture though. And it is flattering to be noticed across languages and oceans.

Anyone here speak Hungarian?

Sunday, October 12, 2008

Dance the map

Gaming: my favorite example of maps functioning fully as fiction. Just as we use cartographic maps as a framework on which to find our way around the real world, gaming maps form a structure for fictional play. But the cartography itself tends to be pretty conventional. The idea is to provide a setting within which gamers can comfortably play.

Theater: Theater actually works pretty well as an analogy for how cartography functions today. There is an artificial representation of setting, which is as detailed as the performance needs to support it. But the problem here is that in the conventional theater setting, performance is distinctly separate from setting. A stage set can be said to “overwhelm” a performance if it dominates, which it should not. This means that voice as an element of setting (or by analogy, of the map) is just not part of the basic conventions.

Performance: In terms of formal structure, the art world has a lot of potential. I and a group of NACIS folk spent a day with Steven Holloway out on Clark Fork in Missoula, and then back in the U of MT printmaking studio pulling monoprints (which was absolutely wonderful; made me want to get back into the print studio. more later on the workshop). Here’s my problem with the artworld as a whole: it feels quite disconnected with how most of the world lives. It’s a little like quietist tendencies in anabaptist circles: if the world won’t be with us, then we will be our own world. What art cartographies I’ve seen have been like dada commentary: pointing to the inherent absurdities of our relationship to earth and place. An important role, yes, but I am interested in insider as well as outsider perspectives. I want to see performative cartography as integral to a place.

Dance: There isn’t a lot of place-dance, which seems weird to me. Formal performance dance (modern, ballet, etc) are relentlessly placeless, formed instead around choreographers and performers who could dance their specific dance in any theater.

There are some extremely place-related ritual dance traditions in older cultures. I think of the 'Obby ‘Oss of Padstow, Cornwall, or the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance. I’ve danced in American renditions of the dance form, and in one case (dancing Abbots Bromley at the Renaissance Festival in Minnesota) it really takes on the feeling of “blessing the place,” as I’ve heard that particular dance called. But the funny thing is, while a pattern has been set of regular performance (annually in all three examples above), there is nothing inherent in the dance that says it must be performed in that specific place. It may be more special or meaningful, but formally, ritual dance is as transferable as modern and ballet dance.

But again, it feels like dance ought to be a good place to start. Dance is so inherently spatial. It is fundamentally about attention paid and patterning formed in space.

Processionals: Parades ought to be place-based. They are in the same place every year, they are often organized for and of the community. But at least the ones I’ve been in are resiliently not about place. In Minnesota, the “royalty” of every little town goes and drives down main street of every other little town on the back of a float. Bands from all over come and march through, various Shriners groups do their thing... it’s fun, but it all ends up kind of generic. And it is certainly never about the space it passes through.

On the other hand, Catholic processions in Mediterranean and Latin American cultures are very specific, as they are tied to specific relics. There are formally similar processions in India (Ratha Yatra with its Jagganath carts, for example), and in Japan. And then there’s the Hajj.

Pilgrimage: The Hajj. Yep, I think we have at least one winner as a model for a performative cartography. Pilgrimages take place over long distances, and their routes are repeated so often and by so many, they become marks on the earth themselves.

Pilgrimage is not a modern idea, and while most of us make pilgrimages of one sort or another, They are rarely approached as such. The annual trip to grandma’s, with stops at that specific scenic overlook or that gas station. Some other momentous trip to a place of reverence (I’m visualizing a trip to the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington). And there are individual traverses: the Appalachian Trail, biking across America...

Interestingly, the most compelling way of talking about pilgrimage in modern culture is not cartography but text, or film. It is through a voiced narrative that we understand this specific narrative. I remember a riveting slide presentation by someone going on the Camino de Santiago in Spain. The setting clearly was important, but it was the total experience, personal social and environmental, that made it compelling.

--------

Cartography separates space from experience, the same way theater separates stage set from performance. I think maybe we need to invent some sort of hybrid form that gives up the conventions of cartography, or anyway a lot of them, to allow for a real performative cartography.

One mode of thinking about this may be to turn the map inside out. Instead of attempting to dance a performance on a published map, make cartographic thinking part of a performance in the real world. The phrase “dance the map” comes to mind. Like processions to mark the parish bounds, perform out the lines we draw.

Over and out for now.

Friday, October 10, 2008

Painless maps and map opera

NACIS is usually my big idea overload binge of the year, and this year was no exception.

Margaret Pearce and Mike Hermann did a really fascinating map of Champlain's travels in Canada, incorporating various kinds of text and map elements in a narrative shape that to me looked a lot like a cartographic attempt at Chris Ware's comic book experiments. But the really funny thing to me is how the whole thing felt like a script (Mike replied he was thinking storyboard, but same basic idea). It's like an outline for some sort of new performative cartography.

What on earth would a post-scientific performative cartography look like? I have no idea. I really am drawing a blank. But I think it is worth considering, and I willl try to suss it out here. I welcome ideas.

------

One of Margaret's students at Ohio U, Karla Sanders, made a fascinating attempt at melding cartography with personal poetic experience of space, a poster titled "When a Mountain Falls to Coal." It looks at the mountains of Appalachia as victims of a destruction created from outside the region, as a sacred space desecrated out of greed. The fundamental problem I have with both the Pearce/Hermann and the Sanders pieces is that they haven't really gotten over the constrictions that cartographic style places on personal expression. The intent is clear, and the text is evocative, but cartography as a mode of communication fights tooth and nail against expressions of personal emotional or spiritual experience. It denies the role of performer as an identifiable part of its performance.

------

A bunch of us went up to the Missoula Art Museum at lunch today to look at a display of Steven Holloway's artwork. Very nice stuff. Neat to see the observation notebook samples in some detail. I don't know how much of the change is NACIS's getting used to Steven, and how much is Steven's mellowing, but the detente between his art and the whole mappy thing seems to be getting closer. Like it's less weird. Anyway, enjoyed the show.

I was feeling a claustrophobic, and so went upstairs to look at parts of this very well put-together little art museum. I was especially struck by the exhibit of contemporary Persian photography. Lots of really powerful stuff. What really struck me looking at it after a few days of looking at maps was the element of pain. We don't show pain in our maps. Steven shows alienation from the land, but not (to my mind) real expressions of pain as such. A cartographic depiction, even of a great wounding of the earth like Sanders' poster, denies pain. It just isn't admissable as a mode of expression.

I think of erin o'Hara slavick's work on bombing we looked at at NACIS last year. Whole lot of pain channeled there, and in her presentation much of us was directed back at us mapmakers. But I want to see a cartography that permits expressions of pain, instead of accusing cartography of inflicting pain. I feel like we're aren't there yet, and beyond everyone's inherent desire (myself included) not to feel pain, I can't see why.

-------

Tomorrow morning at 8am a few us are off on an adventure with Steven to make a map from direct experience. I believe it involves wet and cold. More tomorrow.

Thursday, October 9, 2008

The world's a stage, and we are but poor stagehands

Oddly, what I keep coming back to so far, which has very little to do with any of the conversations I'm actually having, has to do with performance and stage setting. Now, in the Western theatrical tradition, the stage setting ought to be a neutral space for a performance to take place in. A big fancy setting requires a big fancy performance. In other cultures (I'm thinking here for example of the ras lila plays my mom spent some time among in Vrindaban in India), the setting is itself a sort of performance.

My view of how maps work increasingly works with this metaphor. The performance is the specific narrative information, the "story" that is being told. In the case of what we call "reference" maps, that performance is expected to be played out by map users identifying relationships, routes and patterns upon the stage setting of the map. For propaganda and other persuasive maps, the map itself makes a performance, enacting arguments as part of the product.

What Denil, Krygier and Wood and much of the rest of modern cartocriticism all have in common, is the realization that the western idea of separating stage setting from performance is an artificial one. The way we draw the setting for our argument is itself an argument for what background will be used in the discussion.

I still think there is a useful distinction to be made in looking at the stage and the performer as distinct, simply because they are experienced differently. When we look at even a Wagnerian stage setting, a ras lila with flowers pouring from the ceiling for an hour continuously, an evening at Red Rocks, we are in an environment. The performers, on the other hand, we perceive as persons. So perhaps this is a useful distinction: where is the thing we are taking in a "person", and where is it a "non-person."

More food for thought.

Thursday, September 25, 2008

No Man's Land

The phrase "no man's land" popped into my head this morning, and I find it resonating.

What the phrase evokes most of all to me is the dreadful no-man's-lands of World War I, the muddy, bloody plains of death. No man's land is not a place to live in, it's a place to separate peoples who cannot live together. Instead of creating a shared space, it creates an unclaimed space. To be blunt, there is no love there.

I was trying to conjure up an alternative to the scientific, objectivist way of finding common ground, asking "what other common grounds are there?" The obvious one is personal contact. The way you make the stranger into a non-stranger is to spend time with him/her. Host and guest. Or neighbor and neighbor. Not that I really know my neighbors all that well, but communion can be achieved through common work, even among strangers.

The opposite of no man's land then is "the commons" where we all graze our livestock— "we" in this case meaning the shareholders of the commons. Not everyone everywhere, but everyone in the village, everyone working on the same project.

How does a no man's land become a commons? I think of this literally happening in the story of Christmas 1914 in the trenches of World War I, where the guns stopped and soldiers from opposite trenches met, traded songs and cigarettes and played soccer. The story brings tears to my eyes still, like the hopeful/exhausted refrain of the Decemberists' "Sons and Daughters": "here all the bombs fade away..." [actually the lyrics sheet says "Hear all the bombs, they fade away," but I hear otherwise] but that's another blog entry.

But to think of it, Christmas 1914 depended on the majority of soldiers sharing a common religion. They both celebrated Christmas, neither side wanted to be shooting when they would rather have been home with family. I'm guessing things would have been different if the Gallipoli campaign had happened in 1914. But no, a truce to allow clearing of bodies did happen. So sometimes you can appeal to commonality as a species.

No-man's-land implies the opposite of itself—territory. I need to do some studying about the evolution of modern ideas of property and territory, because they clearly aren't universal. Nomadic tribal societies, while they wanted to keep their own hunting grounds for themselves, did not allocate land to individual "owners." And many settled societies have had owners as equivalent to rulers (see lords and serfs). As small freeholdings became more common in Europe, how did the idea of territory change, and when did "commons" arise as an alternative to private property (or is that how it worked at all)? Like I said, I need to learn more. (I note with interest a reference in the wikipedia discussion page on the article Property to "Richard Schlatter's by now classic Private Property: The History of an Idea. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1951, or for a more current perspective Laura Brace's The Politics of Property. Edinburgh University Press, 2004")

So how do you get from no man's land to commons? And (to get back to the general theme of things here), where does the cool light of "objectivity" fit in? The question, I think is to what end neutrality is invoked. By itself, "neutral territory" can mean the no-man's land of World War I; or its cold modern alternative, the DMZ; or Switzerland, or the town common. Is the difference a matter of scale and dispute, or is there something else going on in the range of possibilities?

Tuesday, September 23, 2008

Selective memory

I've been trying to figure out what's really going on here, and not just here but in general in the whole "selectivity" business in college guides and so on. Here's what I think: It is not seemly and polite to talk about a college's "mythos," but that's what's going on. One of the important things about Harvard is that "Harvard Aura" and the same is true of other "selective" institutions. You go there, you know you're hanging out with future Nobel Prize winners, or at least with people who can plausibly sound like future Nobel Prize winners. And this is known in the public at large.

So my question is, how can we talk about this in wikipedia? Some colleges have "Wobegon University in popular culture" sections,but these are mostly lists of mentions on TV. Seems to me this is the place to mention "aura", and in some cases there's specific examples to bring up: Robert Pirsig and the University of Chicago, Paper Chase and Yale. For smaller schools, not so much. I went to Carleton College, which has the reputation as the highest-caliber college in Minnesota. But there's no movie or popular book that backs this up, and no news outlet wants to tick off alumni of other places unnecessarily by saying things like "Minnesota's top college". Maybe reference here to less-rigorous college guides (like College Prowler or The Insider's Guide to the Colleges) is in order, under the rubric of "How Carleton College is talked about," separate from verifiable stats.

The point is, if we can find some way to talk about reputation that isn't the article defining that reputation, I think that will get at a lot of the underlying issues here.

Which gets us right back to "what kinds of things can you put in encyclopedias" or maps or other reference works? By classifying things and then only accepting those classes of information that can be part of a communication pidgin (verifiable, supportable, can-be-agreed upon), we leave out a whole lot. But by including those things, we lose the cross-community communication that reference material allows.

It's a dilemma. Well, its the same damned dilemma I keep talking about here, from another angle.

Sunday, September 14, 2008

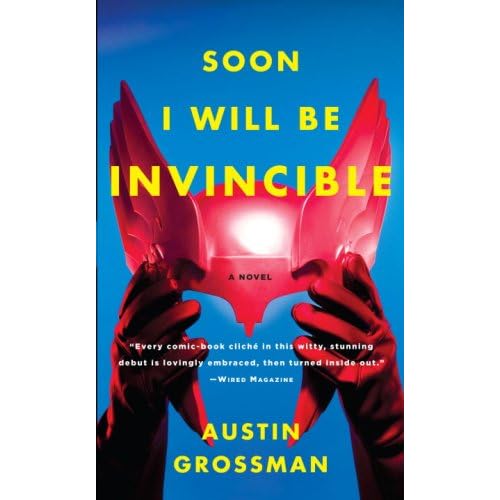

Soon I Will Be Invincible... and all alone

Grossman's take on the whole thing is centered on Dr. Impossible, a beat-up-as-a-kid, misunderstood-genius, superiority-complex/inferiority-complex supervillain...the characters are all familiar, but vaguely familiar. Grossman has done a bang-up job of creating a parallel superhero-infested universe to D.C. and Marvel's trademarked and copyrighted realms.

Anyway, putting it down I was reminded of a pretty much universal theme of modern fiction, how we are all alone. Alienation. Overindividuation. Separation. And so on. It's honestly been a while since I even thought much about it. It's old hat, this alienation thing. It's so, like, 1960.

But, ya know, just be cause it's a cliché doesn't mean it isn't true. Superheroes, or Wicked's witch, just weren't on the cultural radar when Baum's original Wizard of Oz came out. Not that people weren't desperately lonely 100 years ago, but as a cultural theme, it kind of took World War I and the Lost Generation to make alienation interesting. Or normal.

It feels to me like there's a bunch of themes I've been carrying around for long time, some of them for decades even, that come together oddly in the Grossman novel. It's odd to me because, honestly, I've never gotten the appeal of superhero comics. I'm an arty-comic kind of person. Neil Gaiman all the way.

- DIY alienation: I think I've mentioned this before on the blog, how it drives me crazy when people figure they have to "do it themselves" if they are to feel justified in the world. People make fun of Academy Award winners who go on and on thanking everyone, but really they're being realistic. No-one does it alone, and anyone who starts to believe the publicity saying he or she does, is setting themselves for a repeat of Lightning McQueen's situation in Cars. But, of course, we are set up to look at single operators. Soloists are heroes, orchestras are like cabals or gangs. Superheroes are like that false value, magnified.

- Alienation and scale: Superheroes are urban. So are most of us who read this kind of blog-stuff. We have a peer group made up of people "like us" in some respect, rather than family or neighborhood. I know my neighbors, but not well. We don't hang out. My family lives in Maine and New Jersey; my wife's in Colorado and Utah. You get a different story when the characters all have lived in the same town for a long time (you get Garrison Keillor or Louise Erdrich), or if family is what they know and do mainly. And even these non-urban writers can't help but write from a viewpoint where most of the world is urban.

- Alienation, science and universalism: Look, what I'm seeing from where I sit is: there are people for whom God is a person. An all-knowing, all-powerful person, like superheroes are imitations of. And there are others (I'm on this side of the argument), for whom God, or the idea of God, is a map-maker, looking down equally at all points. This point of view does not lend itself to a cozy relationship to the divine, because it includes necessarily the idea that God didn't choose you; you aren't on the "cool" side of God's red velvet rope, because there is no rope. God doesn't choose anyone.

Stray bit: In looking at others' comments tot he book, I really like burritoboy's notes on supervillians as stand-ins for Hitler. Makes a ton of sense; as in so many things, most of the second half of the 20th century is backwash from The War.

Thursday, September 11, 2008

Class

So I've been spending some time working through Jeanne's Social Class and Quakers blog. Not every entry, but trying to get a feeling of where she's coming from.

And I keep getting really ticked off.

Now I like Jeanne, from what I know of her. I like the idea of confronting the cultural claptrap that has nothing to do with the central messages of Quakerism, but which tags along when a group of people from a similar background get together...

No, what gets me specifically is class. I feel like I've specifically tried for much of my life to simultaneously be true to what I am (overeducated, wordy, stuck-in-my-head) and to not get stuck in any class. And not to do the same to other folks. And here I am being labeled "owner class."

I fit the image. I shop at the co-op, read the NY Times, listen to NPR, vote the Democratic ticket... I remember after a long season hopping around doing this and that after moving back to the cities, walking with Ingrid into the Wedge Co-op and breathing in. "Ahh, my people!" I think I said to Ingrid at the time.

But I still rebel at the idea of class. I hate it because it's not a choice. It's like caste in its implications: you were born into it and you will be it until you die. I reject that. I want what I am not to be somehow "symptomatic."

I don't want to be a "type."

-----

Class as such seems too simple. Talking about "owner class" feels like talking about "Black Americans" as if all people descended from African slaves have some gene that makes them all think alike, or for that matter about "Quakerly behavior." Jeanne posed the query of what exactly we mean by that in her latest post.

When I think about "people like me" I think a lot more specifically than "raised with family funds to support me." Specifically, I find myself alienated from people who don't like questions, or who only like safe, cute, or banal expression, or for whom bigger is better. It is a smallish subset of owner class folk who meet that description, and indeed there are plenty of well-educated poor folk who also meet that description.

I clearly need to write up the story of the Tattoo-Rhumba Man. Soon.

Hyphenated Morris Dancers

On Liz Oppenheimer's The Good Raised Up blog, she recently discussed the nature of "hyphenated Quakers" like Buddhist Quakers, pagan Quakers, etc. One of the comments in the thread was Liz's:

The thing I still wrestle with, though, is what to make of--and how to labor with--Friends who are actively engaged in another tradition and who draw on language from or actively request inclusion from a practice other than Quakerism and think nothing of it.In talking about bringing in outside influences, a decidedly non-religious context occurs to me. I'm a morris dancer. We perform dances that were part of specific village traditions. And yet, each team develops specific distinctive stylistic variations based on who the team is. So there's a mixture of "we do it this way because that's how morris dancers do it" and "how about we try this," and thus teams both have a link to tradition and a freshness. In the folk community, the phrase "living tradition" I think sums it up nicely.

The question I ask seeing different morris teams, is are they changing things for the sake of novelty and cleverness, or are they looking for the best dancing they can do? That cleverness is like the "outward forms" that Friends have generally sought to avoid, but as Liz points out throughout her blog and other ministry, this too often been taken as a total abolition of forms, which it is not. Quakers have had a lot of forms, but they were taken up in aid of true connection with Spirit.

There is some of both among formally hyphenated Friends, as well as among those of us who do not have a named second religious tradition to hyphenate to, but who come from outside Quakerism. Some things we hang on to for form's sake or traditions sake, and some things we do because they allow us to come closer to the light.

The question remains from Liz's original question, how do we then apply corporate discernment to practices from outside Quaker practice? For me, one part of that is to encourage more Friends to "own" all their practices, and not let us get away with categorizing things as "our Quaker practices" and "our non-Quaker practices." But the counter to that is to avoid the temptation of too quickly condemning a practice as "unQuakerly" because it falls outside Quaker tradition.

Discernment, discernment, discernment.

The Blind Men, the Elephant and the Narrator.

It’s an old story, much beloved by unviersalists. Some say it’s originally Buddhist, some say it originated with the Jains of India. In any case, it entered western consciousness mainly through a poem by John Godfrey Saxe.

Five (or six, or three) blind men go to see an elephant and decide what it is. One feels the leg and proclaims the elephant a great tree. Another feels the trunk and declares it must be a great serpent. On they go: the ear is like a fan, the tusks like spears, the rail like a rope. The blind men fall into a terrible argument. The moral is clearly drawn: when people talk about the divine, they argue because they all generalize from incomplete information.

The problem with the story is that we all know what an elephant is. The storyteller isn’t blind. Someone is enlightened enough to tell us the whole truth. And that right there is the crux of a big cultural divide: some people believe there really is a storyteller like that, and some believe that all storytellers are just as blind as the blind men.

What makes us “blind” in the metaphorical language of the tale? I think we can divide them into three categories: mortality, individuality, and limited senses.

Our mortality is the great delimiter: we can only learn so much, we can only live so long. There’s a reason immortality is pretty much guaranteed to deities: any being that is immortal, we believe, would have the time to learn everything.

But that assumes truth is separate from point of view. The fact of my independent consciousness, my individuality, means that no matter how long I live, I will not be able to understand all that goes on even for one instant of time. I cannot fully and completely understand my neighbor, let alone all five billion other humans, let alone the points of view of every other being in the universe.

And even if we did see from every other person’s point of view, that point of view only hears and sees certain wavelengths, has a limited sense of smell and taste, and our brain tends to to do a constant filtering job on what sensory input receive, focusing on what we deem “important.” Even if we focus our attention on hearing and seeing more, both important and not, we then lose time to process and understand that input.

All of which leads to a cold, inhospitable sense: we will never really understand the divine. It will always be beyond our reach.

Our religious traditions say otherwise. And that, as I said, is the crux of a conflict.

Religious traditions propose that our soul, our consciousness, is separate from our body; it is immortal, and its limitations are bound up in our physicality. We can free ourselves of that physicality now or after death, and thus be reunited with a more transcendent point of view.

Religious traditions often propose prophets or siddhas or shamans who are like the storyteller. They may or may not transcend death, but they do transcend their mortal bodies to achieve a higher understanding.

And, as the old story goes, if you put enough of them together, they sound like a bunch of blind men arguing about an elephant.

I guess I don't buy it. Some people my develop (or be born with) a longer vision than others, but I can't get myself behind anyone truly developing transcendent consciousness. I think what we see is not a whole elephant, but at most part of one arm. The left elbow of God. The great visionaries may see a shoulder or a wrist, but I think our limitations as mortal, individuated beings with limited senses, bound to our bodies, pretty much mean we can't ever see the whole thing. We can't know how many arms there are, or it there's one head or ten heads or no head.

That's where I am now anyway.

Lone Star Ma commented on June 16:

I am also very universalist and I guess I don't really see it as a conflict so much. I'm happy enough with the elbow and excited about the journey to the shoulder. I think it's more about touching the elephant and trying to understand what the elephant wants of me...

intro to my old Quaker blog

----

I've been meaning to join the Quaker Blogging rounds for a while now. I mostly have lurked, and mostly at blogs by folks from my home meeting like Jeanne and Liz and James. I've been blogging for a couple years at maphead.blogspot.com, which is fun but I feel an urge more and more to drift away from the cartographic focus there, and go on about Quakerly stuff. So, with the miracles of modern technology, here I am.

And here goes.

The biggest thing I've felt myself wrestling with over the last few years on a spiritual level is the apparent divide between universalist and what I'll call specificist ways of approaching spiritual matters. To me these feel like approaching the same point from different directions, and I have spent some time trying to wrap myself around the problem, to find a point of view from which the two can be reconciled.

I grew up unchurched, and with a frankly dismissive attitude towards religion. My high school days at George School were a kind of opening for me; I got to talk about ideas and the shapes of things, in a more-or-less Quaker context. But I ended up deciding I was not with the Quakers because of what I called the Quaker paradox: how do you show tolerance and understanding for those whose explicit message is that you are not legitimate. How should an FGC Quaker deal with a foaming-at-the-mouth millenarian Baptist? What I saw a lot of at George was a dodging of the question... foaming at the mouth got you laughed out of town, and if there was a hint of threat, it got you ridden out of town. I had friends who, well, they didn't foam, but they did dribble, and they were not treated with peace love and understanding by my fellow right-thinking classmates. Who were high school students after all.

Anyway, I wandered hither and yon in college and after, ended up settling with the Unitarians in Excelsior, MN for a few years... a really lovely group, but I found myself missing the sense of a spiritual center.

Four years in Vermont and a marriage that wasn't going so well, and I was asked by a friend to "go do something for myself." Well, I liked Quaker meeting, even if I didn't feel especially Quaker myself, so I started going to Hanover Friends Meeting. After a year I decided I had in fact found my home, and I joined. Moved to the Twin Cities as part of my remarriage, and joined Twin Cities Friends Meeting.

And the Quaker paradox keeps coming back in different forms: how do you reconcile a notion of universal love and tolerance—of eight blind men making their way around an elephant—with the undeniable need of individuals to recognize specific experiences, and to form groups based on common identity.

So that's what I plan on writing about here.

Sunday, September 7, 2008

identity grid

I think it's interesting how in the world of people who make things for money, you can divide their self-definitions two ways: definition by what sort of subject-matter they choose, and definition by what sort of medium they work in. In the arts, this means you're a portraitist or a painter; in graphic design it means you're a cartographer or a book designer; in writing it means you're a financial writer or a journalist.

In any of these examples, there are conventions, there is a sense of commonality of language and understanding when two or more people of like self-identity meet. The narrower the common self-definition (financial ceramicisists working in terracotta mergers and acquisitions), the more they will share a network of shared experience and understanding. And the closer they get to having the same experiences in their work, the better the chance that their conversation will move from "isn't that interesting what you're doing over there" to "don't poach my turf." When two people interested in the same things realize they're fighting for work the same clients. Or the same tenure committee. When one or both of them decide the town ain't big enough for both of them.

----

I'm trying out the thesis developed in the discussion over the Grid (in cartographic terms), that the problem isn't in the gridding per se, its in the reimposition of that grid back on the subject. Does that apply to identity? I'm thinking of ongoing discussions in meeting about Quaker identity, but I think it applies to all identity groups: Is the problem less with the identity group and more with when the code which binds us is then reimposed back on us?

We human beings come up with structures, codes, grids, networks, any numbers of systems we lay our understandings of the world over the top of. Saying we shouldn't do that because systems end up dividing us is like saying we should stop using language because we'll be misunderstood.

We also like to form community (or better yet find community, because its easier) around identity, to be able to say "these are my people." And it seems sensible then to put these two together, and to codify what it is that brings us together. Maybe it's a hierarchy (I'm with you because of a feudal system, or because we're part of this family tree). Maybe it's a creed (I agree with enough of the planks in your platform, I'm in). Maybe it's just cultural clues (You like chicken? I like chicken!). Maybe it's a bunch of people who all know the same songs (I know I'm not the only one who had a near-religious experience at a Pete Seeger concert).

But...

The problem arises (I would submit) when we then look at the "official" set of common-identity markers, and judge ourselves (or worse, allow others in the group to judge us) based on our adherence to those markers. To make the Grid the marker of value, not the thing itself.

Friday, August 8, 2008

Theological diversity

I was reading Joe's excellent comment tonight while gearing up for a session on "theological diversity" at Meeting tomorrow. In our meeting (and among FGC Friends in general) there's been a resurgence over the last decade or so in Jesus-centered worship and ministry. For those of us for whom Jesus is not the central exemplar and teacher, and who may have signed on with the Quakers to get away from dogmatic Christians, it's been a little weird. But that resurgence has in my experience been gentle, not prosletyzing, not hegemonistic. It has all been about individuals being open about the center of their universe.

To me it feels like the shoe is now on our foot (those of us who have held a more universalist point of view), to come clean about our centers, instead of using old hegemonizing, power-grabby, churchy attitudes as straw-men. The Bible doesn't especially speak to you as scripture? OK, then what does speak to you as scripture? Outward religious ritual isn't your thing? What formal, regular recognition of the universe and where we fit in it does, then?

Where this fits into the discussion of maps and architecture, is that I think it presents a model for how to carry that balancing act forward. The argument shouldn't be between objectivists and subjectivists. It shouldn't even really be an argument at all. The work as I'm coming to see it, is to theoretically explore how those two ways of dealing with the universe interact, and build practices that respect each. And that involves (as a cartographer) simultaneously respecting the traditions and knowledge we've built up over the centuries, and recognizing that cartography is (and when used properly only can be) a structure, upon which centers can be constructed. Instead of isolating ourselves from that center-building, we need to really look at how we can be part of the subjective, center-building, all-too-human process of Making the World.

Wednesday, August 6, 2008

Steig said it all

Art, including juvenile literature, has the power to make any spot on earth the living center of the universe; and unlike science, which often gives us the illusion of understanding things we really do not understand, it helps us to know life in a way that still keeps before us the mystery of things. It enhances the sense of wonder. And wonder is respect for life. Art also stimulates the adventurousness and the playfulness that keep us moving in a lively way and that lead to useful discovery.So there you are.