We're working our way through the Harry Potter series; a few nights ago we reached the climax of book 6, the battle on top of the tallest tower in Hogwarts, with its unexpected conclusion. Our son has been very anxious about what happens next, who dies, who lives... and he is a kid who is pretty good about fact and fiction (I expect, when the time comes, that he'll take the unmasking of Santa Claus, Easter Bunny and Tooth Fairy pretty well). And he really gets riled up—and so do we all, when we let ourselves be taken over by a fiction.

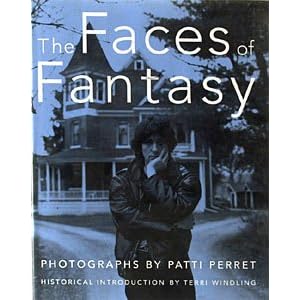

A month or so ago, I picked up a great coffee-table book at a used bookstore in Duluth. It's called Faces of Fantasy, and the most fascinating thing about it, I think, is the degree to which some of the authors admit having magic invade their world, after having spent so much of their lives honing the craft of describing magic in fiction. Not all the writers; some are pretty blasé about what they write, if gracious at having been allowed to make a living having so much fun. And some are so into the sheer Gothicness of writing fantasy as to be laugh-out-loud funny ("Worship me, mere mortals, for I am the Bride of Jim Morrison!" Seriously.). But the authors whose books I most enjoy are thoughtful about the ways that their storytelling work remakes the world, unmasks secrets inside readers, tells stories about the heart of the universe.

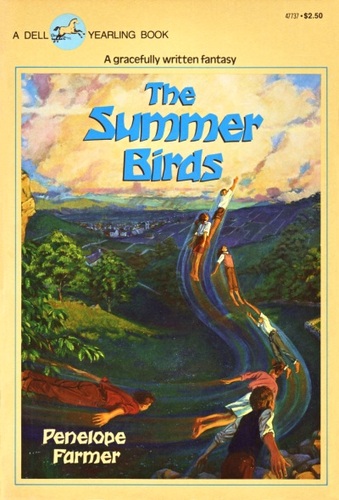

As a child, I loved fantasy, and I never totally outgrew it. I think I've mentioned this before. As I grew up, I found ways to get "serious" about my interest, to justify it somehow, but... I recently re-read one of my early favorites, The Summer Birds by Penelope Farmer. I think I can finally admit that plain and simple I loved those stories for the vicarious experience of magic—a kind of hair-tingling, heart-pumping exhilaration. Just the idea that a kid could learn to fly. As I said a couple weeks ago in meeting, these were my miracle stories.

I wrote a couple of years ago about my time in the world of fantasy fiction as a young adult, and how I was kind of surprised to find the creators of these stories not to actually be wizards or Illuminati or whatever. But in reading Faces of Fantasy I see a sentiment among the writers I respect most that is a little like the Quaker line I keep coming back to, about how we abolished not the clergy but the laity. The point is that these writers are not trying to gather magical knowledge in order to empower themselves over others—they are trying to spread a sense of magic diffusely, to reintroduce it back into a culture that frankly doesn't know what to do with miracle stories. Which in turn reminds me of the interesting discussion on the Sheffield Quakers blog which eventually turned to the idea of magic in Quakerism.

Again, as I said in meeting, we Friends don't do miracle stories much. We try to be reasonable, and we try to speak truly from our experience. And I venture to say none of us has had experiences identical to the ones in miracle stories, old or new: literally walking on water, literally flying like a bird, literally returning from the dead.

When I've tried in the past to look critically at fantasy stories, I've tried to figure out what magic means in modern kids' fantasy fiction. Creativity, or aliveness to the world, maybe. Power, in some books. But what I'm seeing in revisiting the topic after some time away, is that fantasy books are, at heart, about Amazing Things Happening. How do Amazing Things change us? How do they pull us away from those who haven't experienced them? How do they push us to attempt Amazing Feats ourselves? How do they clarify the world, and how do they make it more confusing? And so on.

And here I go back to a line of questions I started asking when I first becoming a cartographer. At the time, I asked "Can a map be an independent work of fiction?" My conclusion is that while they can be used as part of a fictional game, or as an illustration to a work of fiction, maps can't stand on their own as works of fiction, because they don't stand on their own as works of fact. They need to refer to the real world in order to fulfill their purpose.

What about miracle maps? What would a miracle map be? I ask without a clear answer. But it's an interesting question.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

I too am a great lover of fantasy, especially that written for children. I also admit that I have been wary of maps since I do not immediately understand them and must make quite an effort. But there is a map I have always loved and that was the map of Narnia and the surrounding seas and countries of that magical land. I suspect that it is this map, and the stories that belong to it, that helped shape my understanding of sacred geography and my sense that story and land, miracle and memory all belong together.

Post a Comment